The notion of bonds as a hedge to equity has long sat at the heart of asset allocation. The financial crisis has, however, tested the old relationship as central banks embarked on massive bond buying programmes. With central banks so massively extended, and the perception of Western sovereign debt as riskfree dying off, the relationship may have changed forever.

“The risk on/risk off approach of recent years, which is directly attributal to the manipulation of all asset prices by central banks, has tended to see equities and bonds rise and fall together.”

Olivier Lebleu

The relationship between bonds and equities is like marmite for institutions, especially DB pension plans – they love it or hate it. On the asset side, when the hedge works, the negative correlation between bond prices and equities provides capital protection as risk assets fall. For liabilities however, the positive correlation between yields and equities means funding gaps look bigger as capital losses bite. The correlation outlook is therefore fundamentally important to how those institutions manage their assets and liabilities. This fact could, in itself, change the path of yield normalisation in the coming years.

With the beginning of the end of QE in sight, investors are left asking themselves whether the correlation will revert to traditional norms or whether the marriage between bonds and equities is permanently broken. Will bonds still provide a hedge to equity?

Regime change

Bonds and equities have not always been negatively correlated. Before the early 1970s, the opposite was true.

Pre-1973, in the Bretton Woods era, central banks’ efforts to control inflation were constrained by the fixed exchange rate regime. 1973 also saw the oil-price shock where inflation increased and both bond and equity returns were poor. The positive correlation remained through much of the the Great Moderation largely because the world was dominated by inflation shocks.

The demise of Bretton Woods gave central banks the flexibility to shift from controlling exchange rates to inflation, a strategy that became increasingly credible in the late 90s.

“The world changed, statistically speaking, in 1998 following the Russian Crisis, which was the first time we saw bonds and equities go in different directions,” says Richard Urwin, managing director, head of investments at Blackrock. “The late 90s saw an end to developed economies being dominated by inflation shocks as inflation stabilised. Correlations became driven instead by growth shocks of either extreme recession or extreme recovery. In that environment, what is good for bonds is bad for equity so the correlation is negative.”

Central banks still target inflation, either implicitly such as the US, or explicitly as with the UK and Europe. The current period of all-time low interest rates suggests correlations between bond and equity prices should be negative with interest rates likely to increase as much-sought-after growth returns. This suggests the case for bonds as a hedge to equity risk should remain largely in place over the long term.

“Markets are convinced central banks’ mandate of targeting inflation is still valid,” Urwin says. “Looking at what is priced in to inflation-linked bonds, the inflation targets set by central banks still dominate. We would need a powerful regime change to alter that.”

The great manipulation

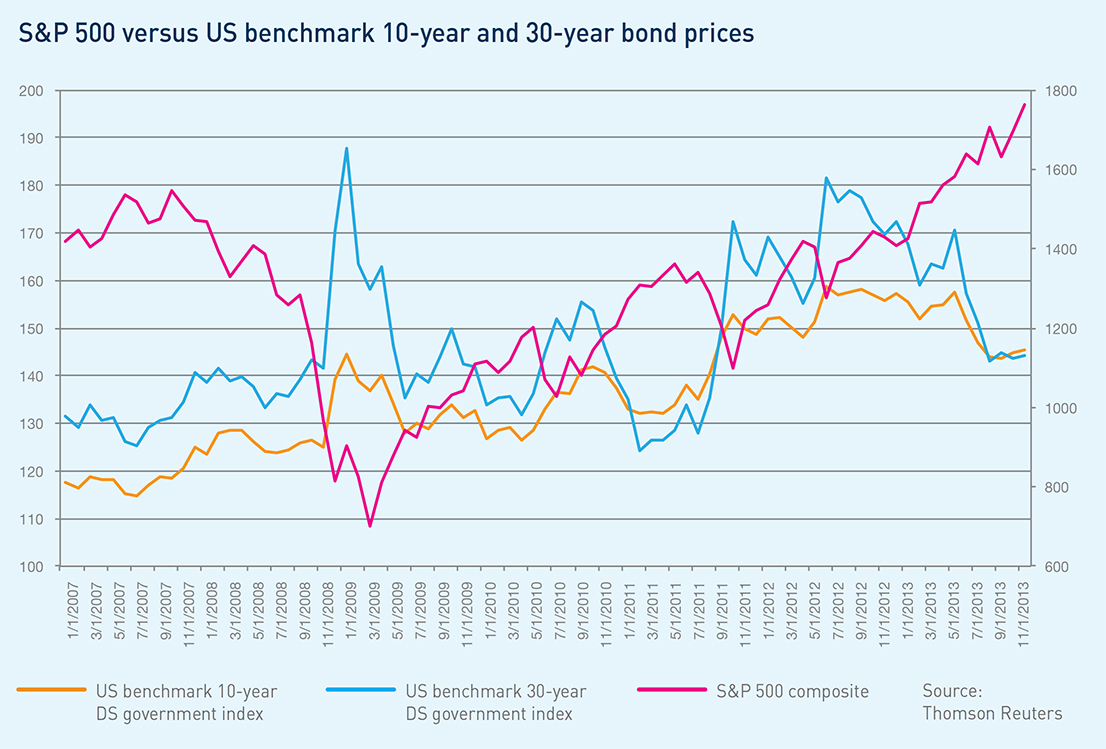

What markets have not been so convinced about, however, is the massive bond-buying binge many central banks have embarked on in recent years. The result has been to reverse the normal correlation between bonds and equity.

QE has artificially forced yields down, pushing equity and bond prices up at the same time. It has also left markets uncertain and nervous.

“The risk on/risk off of recent years, which is directly attributable to the manipulation of all asset prices by central banks, has tended to see equities and bonds rise and fall together,” says Olivier Lebleu, head of non US distribution for Old Mutual Asset Management International.

Comments