In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

28 Oct 2016

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

18 Oct 2016

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

In the first of three articles looking at scheme funding, Con Keating laments the current approach to measuring and hedging liabilities.

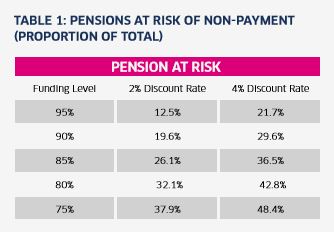

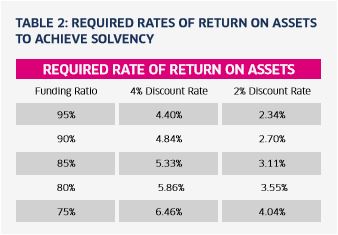

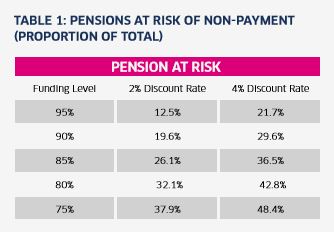

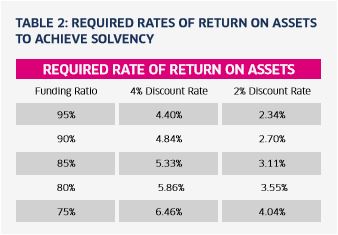

For many years I have railed against the use of discounted present values and solvency-type approaches for pension schemes. These have led to such nonsenses as “liability driven investment” which are actually hedging the measure, the discount function rate being applied to liability projections rather than any of the true risk factors which determine actual liabilities. Even though wrong, the narrative has been overwhelming; this is ‘hedging liabilities’, when it is, in fact, the present value of liability projections. This behaviour may, in part, be explained by a feature of the theory of motivated reasoning, the desire for belief consonance; people really do become uncomfortable when they are aware that their beliefs and actions differ from those of their peers.This narrative has been reinforced by the dominance of the solvency ratio in regulation and scheme status evaluation; an available statistic that is close to useless as an indicator of the value of pensions at risk. The proportions of pensions at risk of non-payment, after all funding has been distributed as pension payments, for an illustrative scheme, for a range of funding ratios under 2% and 4% discount rates can be seen in the table inset.There are other measures that are informative, such as the related time to exhaustion of current funding, the time to default, which is a measure of the time available for deficit remedy. In this illustrative case, it varies from 18 to 35 years. There are further issues with the use of funding ratios as risk measures; a 5% change in the funding ratio returns non-linear context specific changes in funding sufficiency. The problems are even theoretical; under the standard log-normal model of asset and liability prices the funding ratio would be Cauchy-distributed and lack even a well-defined mean.It is clear that there is now only one dominant narrative, which should surprise and worry us given the inherent, irreducible uncertainty that always surrounds pensions, and the heterogeneity of trustee boards, schemes, and their sponsors. This is motivated reasoning at work. The narrative is persistent; deficit figures are brushed off and trotted out by journalists whenever there is a shortage of real news, and invariably described as liabilities. These serve to buttress belief in the decisions already made, which is itself surprising as expected events carry little or no new information. Contrary evidence is dismissed, a classic symptom of folly, which has been well described as a “refusal to draw conclusions from the evidence, addiction to the counterproductive.”Even developments which are the direct causal consequences of prior decisions and action, such as the commonly arising negative net cash-flows due to pension payments after closure to new members and further accrual, are considered narrative proof of the dire situation and offered in support of those earlier decisions. There is some hope; recognition of the inherent uncertainty, the indeterminacy of our knowledge of the state of affairs has found authoritative support in the US Federal Reserve “Nowcasts” of economic activity. The problem is greater than simply finding better coincident indicators or correcting for the errors in measurement of funds.There is, though, one particularly informative metric which may easily be calculated; this is the required rate of return on assets to achieve solvency. This is tabulated below for the earlier range of funding ratios and discount rates. This scheme requires the same 4.4% return on assets when it is 95% funded using a 4% discount rate, as when it is 71.5% funded using a 2% discount rate.The scheme in this illustrative case has a funding ratio of 80%; it needs to earn a return of 3.55% to meet all pension liabilities. The asset portfolio, in fact, has an income yield of 4.01%. Scheme assets have delivered returns lower than 3.55% in just six years in its 131-year life; it has never in any three-year period failed to achieve more than this nominal return. The more general point here is that we can ask, both qualitatively and quantitatively, how likely is this return to be achieved or surpassed in the future, to a range of horizons.The demonisation of DB pensions goes far beyond this belief that deficits or funding ratios are good evidence and valid action points for management decisions; it extends to the governance and management of corporate sponsors. We see deficits compared with dividends paid in the year – in one recent study of the FTSE 100, the 56 companies with deficits totalling £42.3bn paid dividends of £53.0bn, repeating the elementary error of economic analysis of comparing stocks with flows.Another favourite distortion is the comparison of accounting ‘liabilities’ with market capitalisations – “the average FTSE 100 company’s pension liability was 34% of its market capitalisation”, which rather loses impact when deficits are compared to market capitalisation – just 4% – and entirely loses meaning when we recognise that, in theory at least, the market capitalisation arises after shareholders have considered these liabilities.Obviously the strength of the sponsor covenant is a material concern for trustee boards, but the assessment of that requires a very different set of metrics from these. There is no mention that the UK private non-financial sector has been earning good and increasing returns on capital employed (12.2% p.a. in the most recent quarter) or that the dividends in 2015 were markedly higher than 2014, and that those pension funds still holding equity have benefitted from the higher cash flow; inconvenient evidence is ignored.The main take-away from this article should be that we need, at the least, to view our pension schemes and their funding status from multiple standpoints, if we are to have a solid base for our management decisions.The DC problem is rather different; with the absence of explicit liabilities, value for money becomes a relevant concern. Value for money is a simple efficiency measure; the ratio of the output to the input. It does not require knowledge of the intermediate production process with its costs and fees; though that is necessary for any intentional improvement of production efficiency. If compound or geometric returns are utilised, the measure reflects and contains the riskiness of the production process. One caution is relevant, which applies to irreversible decisions, such as annuity purchases; even for risk neutral actors, the expected value may not be the appropriate decision criterion.Parts two and three of this article consider further instances of motivated reasoning in pension scheme and fund management and suggest some possible coping mechanisms.“The narrative is persistent; deficit figures are brushed off and trotted out by journalists whenever there is a shortage of real news, and invariably described as liabilities.”

Con Keating

12 Mar 2025

12 Mar 2025

19 Feb 2025

19 Feb 2025

Sign up to the portfolio institutional newsletter to receive a weekly update with our latest features, interviews, ESG content, opinion, roundtables and event invites. Institutional investors also qualify for a free-of-charge magazine subscription.