The recent return to form by CTAs has Emma Cusworth questioning whether their rollercoaster performance in recent years was due to a broken model or simply a lack of understanding among investors.

“Central banks are a powerful force in the existence and creation of trends. Yet, from 2011 there was no divergence in central bank policy. Low rate policies persisted in Japan, Europe and the US so asset classes like currencies and commodities were not moving.”

Steeve Brument

Commodity Trading Advisers (CTAs) returned to form in stellar fashion at the end of last year, ending a three-year period of drawndowns with many posting returns in excess of 30% for 2014.

Yet, in the preceding years, many commentators had begun to question whether the CTA model was broken – were there simply too many CTAs chasing the same things, making it impossible for any of them to generate significant returns? Last year appears to have proven the model is still alive and well, but investors’ understanding of these systematic, typically trend-following strategies is in fact what is lacking.

“Many investors bailed out of systematic macro trading in 2014 only to miss out on a period of exceptionally good performance,” according to Ewan Kirk, CIO of Cantab Capital.

WHAT GOES UP, MUST COME DOWN AND VICE VERSA

During 2008 CTAs posted strong returns. The Newedge CTA index, which tracks the 20 largest funds in the space, recorded the average returns of its constituents as 13.07% while the BarclayHedge CTA index, which tracks a much wider group of funds, gained 14.09% for the year.

Following this strong performance, institutions piled into the space, drawn in by what appeared to be a strong diversification play that could protect portfolios in times of stress.

“After the crisis some less experienced investors saw the good performance the strategy posted in 2008 and saw it as a cheap hedge,” says Laurent Le Saint, head of development, multi-asset, at Lyxor Asset Management. “They were effectively buying it as a put option.”

During 2009 BarclayHedge data shows CTA industry assets increased from $196bn to $214bn, only to rise again during each of the following four years to $268bn in 2010, $314bn in 2011, $330bn in 2012 and hit a peak of $337bn in the first quarter of 2013. Yet, during that four-year period, CTA industry returns had gone in the opposite direction. The BarclayHedge CTA index closed 2009 flat, rose 7% in 2010, but subsequently embarked on a three-year losing streak, tumbling over 3% in 2011, another 1.7% in 2012 and 1.42% in 2013.

Disappointed by the loss of form, investors began pulling money in 2013. Assets fell 7% from their Q1 2013 peak to bottom out at $313bn in the third quarter of 2014, according to BarclayHedge.

Eurekahedge reports CTAs saw 10 months of consecutive outflows by March 2014, suffering outflows of $5.3bn in the first quarter of the year alone.

Then, towards the end of last year CTAs began to post significant gains, driven in large part by the appreciation of the US dollar and the massive fall in the oil price. CTAs ended the year with five months of positive performance, taking the Newedge CTA index up 16% for the year.

Some funds did far better. Stanley Fink’s International Standard Asset Management smashed through 62% over the year, Cantab’s quantitative programme was up 39%, GSA’s Trend Risk Premium fund was up 33%, Lynx gained 28% and AHL’s Evolution fund posted 20.3% gains, to name but a few.

And the winning streak continued into 2015. The Newedge CTA index was up another 2.9% by the end of April, while the BarclayHedge CTA index clocked gains of over 3.4% to 3 May.

With investors buying into a strategy once it had already peaked post-crisis and then cashing out once it had bottomed out (or in some cases was already back on the rise), the obvious question is how investors managed to get this so wrong? Did they simply misunderstand how CTAs are supposed to perform? Is this just another example of how behavioural biases lead to buying high and selling low?

“A lot of the investors that jumped into CTAs in 2009 didn’t fully understand what makes the strategy perform or not,” says Steeve Brument, head of systematic funds at Candriam Investors Group.

WHY DID CTAs FALTER?

This can only be the case if the prolonged period of underperformance made sense. “The basics of the strategy are fairly simple,” says Lyxor’s Le Saint. “They are trying to spot up or down trends using quantitative models and take long or short bets accordingly.”

In the context of four down years in five for the strategy and the longest and deepest peak-to-trough drawdown in the industry’s history, many commentators began to ask if the CTA model was simply broken. Their arguments focused mainly on the question of whether the significant flow of assets into the space had ultimately left it so capacity constrained, particularly in the commodities markets, it could no longer function properly.

But this argument fails to explain the problem adequately. While AUM had undoubtedly increased massively, so had the size of the futures markets and strategies had adapted to deal with the greater trading by CTAs in order to hide their patterns from potential front-runners.

Instead of the CTA models being broken, it was the market that had stopped working. Trend followers still make up the vast bulk of the CTA space, a factor that was even more pronounced at the start of the period of underperformance. Yet, with the advent of massive quantitative easing in global markets, the trends these strategies rely on to make returns simply disappeared.

According to Candriam’s Brument: “The conditions in which CTAs outperform are where markets see low levels of correlations and where trends are present and sustained. 2008 saw a powerful trend as most asset classes exhibited strong trends. In 2009, those trends reversed again and many CTAs were caught off guard so they had a more difficult year; 2010 was positive for CTAs on the whole, but 2011 saw the arrival of a period of sharp risk on/risk off trading, which lasted until mid 2014.”

In 2008 market correlations went “through the roof,” as Societe General Prime Services’ (which now owns Newedge) global head of alternative investment solutions, Duncan Crawford, puts it. However, the correlations between markets is a key component of CTAs’ portfolio construction methodology as they tend to trade a large number of markets across multiple asset classes.

“There weren’t many trades out there,” Crawford continues. “Diversification disappeared. Risks are much higher if everything is moving together and the key to trend-following making money is diversification. When markets are highly correlated, there is much less diversification.”

Newedge’s data shows one-year rolling absolute average pairwise correlation of the 55 futures markets traded by the Newedge Trend Indicator doubled between mid- 2007 and its peak of 0.42 in August 2009 and stayed elevated through to until last year.

The constant stop-start whipsaw of the risk on/risk off period also meant few trends ever really got going, often stopping and reversing before many of the systematic programmes designed to latch on to them could make any headway.

Because of the whipsaw in investor sentiment triggered by the European debt crisis, markets showed a distinct lack of trends and remained highly-correlated in unison during 2011 and 2012.

According to Lyxor’s Le Saint, trends were frequently interrupted by political interventions, and all markets were impacted at the same time. “In other words,” he says, “when the strategy was wrong on one trade, it was likely to be wrong on many other trades.”

But perhaps most powerfully, central bank activity dampened volatility, killing off the trends many CTAs rely on to generate performance.

“Central banks are a powerful force in the existence and creation of trends,” explains Brument. “Yet, from 2011 onwards, there was no divergence in central bank policy. Low-rate policies persisted in Japan, Europe and the US so asset classes like currencies and commodities were not moving.”

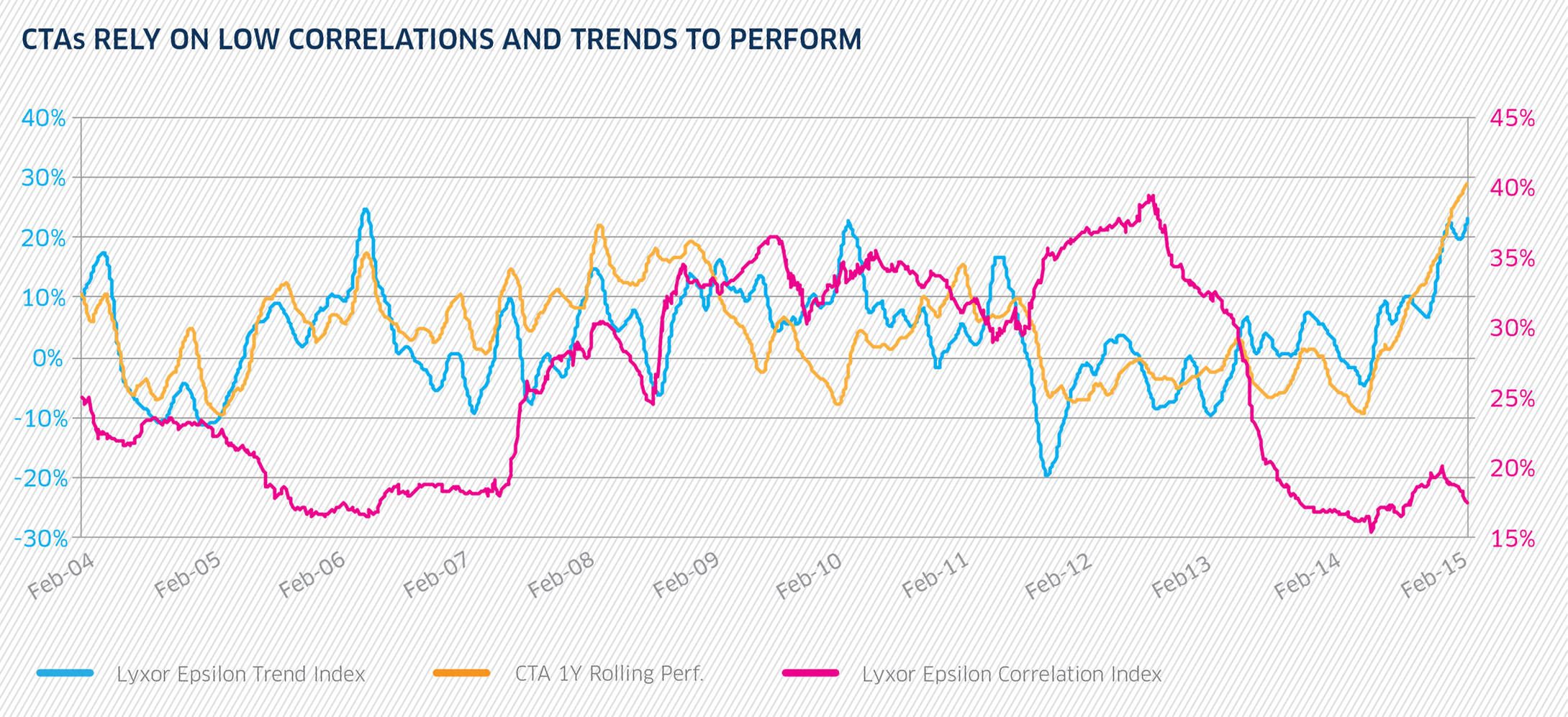

Particularly once the eurozone crisis passed its 2011 peak and central banks continued their aggressive balance sheet expansion, volatility fell away creating a prolonged period of historically low volatility, leaving a void of trends for CTAs to exploit. The Lyxor Epsilon Trend index plummeted from 16% in June 2011 to a trough at -19% in November 2011 (see chart inset). Although it subsequently rose some way, it remained low until mid-2014. And CTAs’ one-year rolling returns tracked the trend index along its path.

So rather than being the put option some investors had expected CTAs’ to be, they very much behaved as they would be expected to – underperforming in a period where high correlations undermined diversification and trends, whether up or down, all but disappeared.

The disappointment with CTA performance is arguably, therefore, more to do with investors’ understanding than with the strategy failing to do as it said it would on the tin.

RETURN TO FORM

In mid-2014, however, markets fundamentally changed, much to the favour of CTAs. Correlations had already started to come down markedly since their peak in August 2012, bringing much-needed diversification back into markets. The Lyxor Epsilon Correlation index fell from a peak of 39% that month to 15% in June 2014.

And at that point, as markets came out from central bank oppression and once again began to move in a more normal manner, trends once again began to take hold and gain momentum. The Lyxor Epsilon Trend index rose from its June 2014 low of 8% to 21% by March 2015.

Not only did the US dollar begin to appreciate in a world that looked increasingly like it was on a path to normalisation, a war for market-share broke out in the global energy markets driving oil prices on a sharp downward trend.

Accordingly Lyxor’s data shows one-year rolling CTA performance rose from -4.6% in May 2014 to +23% in March 2015.

“To make money in CTAs,” Newedge’s Crawford says, “you need low correlations, trends and volatility. While volatility has still not come back yet, trends are expected to continue and correlations have come down so the all-important factors are back in place for CTAs.”

WHERE IT FITS IN PORTFOLIOS

JLT Employee Benefits investment consultant Guy Hopgood reports seeing interest coming back after CTAs posted positive returns and as equity markets look fair or over priced.

“Investors are looking for downside protection if equities fall and how to take advantage of that reversal,” he says.

However, to avoid disappointment it is critical investors understand the mechanics of how CTA strategies work and appreciate that they are uncorrelated, rather than negatively correlated, to equity markets.

Cantab’s Kirk believes: “Many investors misunderstand the role of CTAs in an institutional portfolio. Over time, CTAs have shown that they deliver not only positive returns but returns that are uncorrelated to traditional asset classes.”

As such the addition of CTAs can significantly improve the quality of the overall portfolio. However they do not act as a hedge to traditional asset classes.

“Timing CTAs is notoriously difficult,” Kirk continues, “and there is a very large body of evidence to show that it is in fact impossible. Therefore, like all diversifying investments, they need to be held for the longer term.”

In order to avoid another round of buying high and selling low, investors looking at CTAs today will need to gain a deeper knowledge of the space, which should, in turn, give them the conviction to stand by their allocations should another period of drawdowns hit.

JLT’s Hopgood says: “There is certainly an educational challenge ahead as investors need a better understanding of exactly how they can expect these strategies to behave in all types of markets.”

Comments